LEARNING TO CAPTURE GOOD WILDLIFE IMAGES

By Jane Jamison

When I registered with Photo Workshop Adventures Shetland Islands Adventure in 2013, I was totally ignorant of the daunting task I was attempting. I had just become interested in photography following my retirement and had been on one PWA Adventure in Arizona. However, I had seen some images of puffins and have family living in Edinburgh; so I thought exploring Scotland and the Shetland Islands would be fun. Little did expert wildlife photographer Johan Siggesson know that he was getting a total neophyte to mentor for a week in this isolated environment! He learned, though, that I was interested, took directions well, and was willing to say “Sure” to every one of his requests that began with “Do you want to …..?” This could mean climbing down a steep cliff, choosing the upper deck of a small cruise boat (where I was supposed to take photos while the boat lurched in the North Sea and I was on a swivel seat), or agreeing to “re-do” puffin shots on a blustery, rainy, gale-force windy day.

I had a Canon EOS Rebel T5i with a Tamron 18-270mm travel lens as my only gear. The first two lessons I learned were that wind is good because it gives the photographer a couple of extra seconds to focus and shoot while the bird “floats” on the wind and that I needed to have only one focal point. The latter lesson came when Johan determined my initial shots were “fuzzy” because I had left my camera setting on multiple focal points when moving from landscape photography in France to birds in the Shetlands. I had already followed his direction to change from aperture preferred to shutter priority with a fast setting since most birds are, by nature, flying or moving. The other necessity is continuous shooting mode in order to try to catch the bird or fast-moving animal in at least one desirable position. When shooting photos of Artic terns flying over a rocky field—hundreds of them against a clear blue sky, Johan’s direction was “Focus on the eye and track one bird.” Right!

He captured an image of me stretched out on the rocky ground as I carefully tried to follow his directions. I was amazed with several shots I got that day, building my confidence and surprising Johan with a coveted “beaking shot.”

I learned a lot about animal behavior as well as photography tips. For example, I usually switched to aperture priority for those not very active—i.e., sheep resting on the cliffs.

His further advice was to try to have some space showing an animal’s legs against the horizon—if the animal is standing. Johan was a master at mimicking animal sounds to get eye contact and getting low to the animal’s level. I’m glad I agreed to the “do-over” of puffins at the end of our week when we returned from Hermaness in “the north” to Sumbaugh. I claim my favorite puffin image near his burrow was possible only because I frightened him with my flapping blue poncho as I tried to stay dry in the storm.

Raindrops are visible on his back as he heads for his home burrow (usually a pretty secretive spot that we don’t get to see).

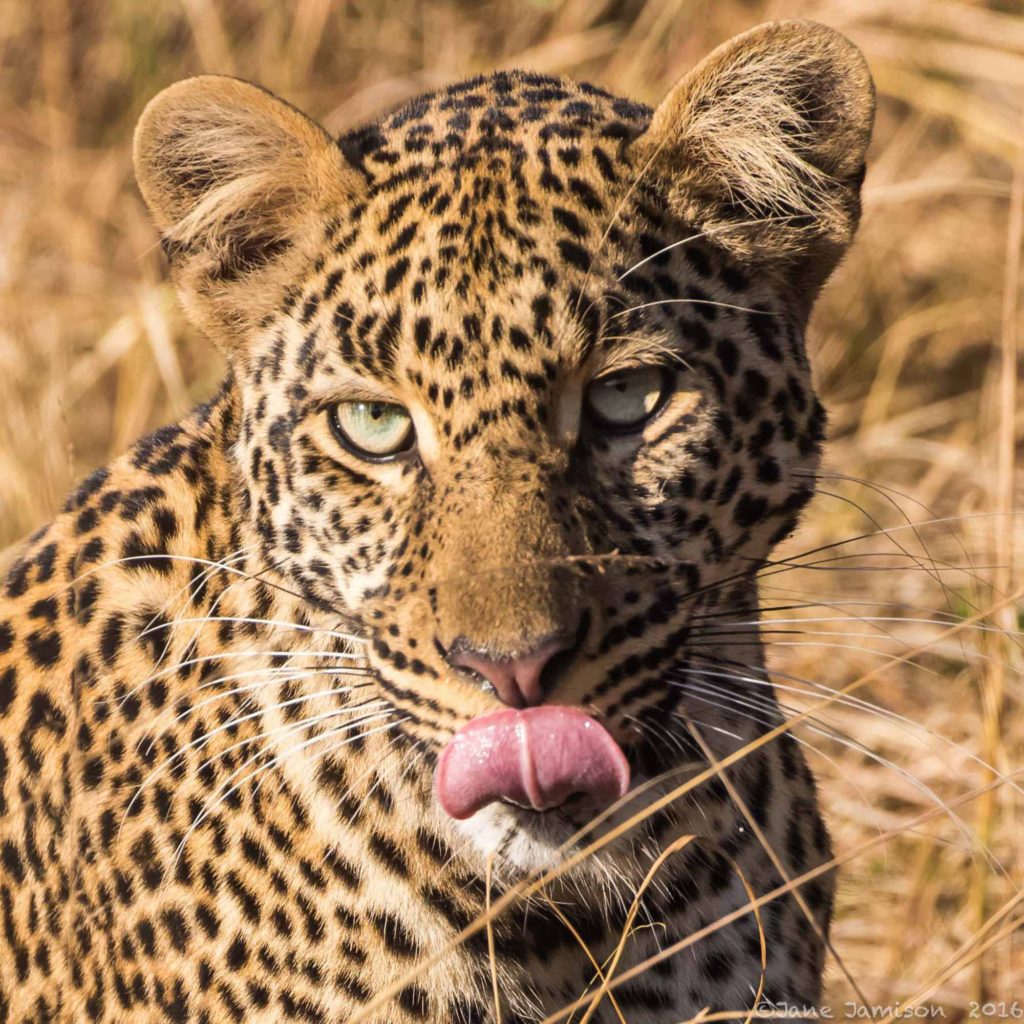

Fast forward to 2016 when, after completing three other PWA Adventures during which I learned a bit more about the mechanics of photography, I again went with PWA and Johan—this time to Kenya’s Maasai Mara. Renting a Canon 100-400mm lens for my EOS Rebel T5i, I was determined to have sharp images, remembering Johan’s standards. His guidance for this experience was quite different since we were dealing with larger wildlife, most of which moved slowly, if at all. He advised aperture priority setting with a fairly wide aperture—f5.6-6.3, give or take—with a single focal point on the eye of the animal in order to have appropriate depth of field and focus. The only settings I had to adjust were the exposure compensation (to handle the “before daylight” and “after sunset” shots) and the metering for backlighting or sunrises/sunsets.

In that case, I again used continuous shooting; otherwise, I chose single shot. Johan’s advice helped us focus on and enjoy the animals rather than worry about camera settings. Because we were in vehicles where there was no room for tripods, the camp provided rice or sand bags for stabilizing our cameras/lenses. I was too short to get a good angle with this device even standing on the seat and shooting out the top; so virtually all of my Kenya photos were taken handheld.

Having no particular time limits, we were able to watch animal families interact, beautiful creatures stalk and capture prey, and thousands of wildebeests prepare for and execute “crossings.” Capturing these and other images was made easy by PWA’s expert wildlife mentor, Johan; the small group size; the Entim Camp itself with its luxury tents; and our driver (John), who was a master at finding potential subjects.

Lessons learned on these two PWA adventures have stayed with me. As I visited family in South Carolina this spring, I had the opportunity to observe and capture images of alligators and seabirds (herons, egrets, roseate spoonbills and others). Using my newly purchased Fujifilm X-T2, I was pleased with its performance as well as that of these fascinating creatures.

If wildlife photography interests you, check out PWA’s Kenya Maasai Mara Photo Safari Adventure. It will not disappoint you.

May all who come as guests… leave as friends®